The World of Goods: Toward an Anthropology of Consumption (1996 [1979])

By Mary Douglas and Baron Isherwood

Synopsis: This book is an attempt to bridge the gap between economics and anthropology by arguing that the "idea of consumption itself has to be set back into the social process, not merely looked upon as a result or objective of work" (viii). This is a critique of materialist views, and takes a very anthropological approach. The book is divided into two parts: Part I: Goods as Info System, and Part II: Implications For Social Policy. The main argument is that goods are primarily a function of social relations, and are markers of rational categories. Goods are part of a live information system, hence our ability to access and produce "information" is key. Consumption decisions define our culture, and commodities are nonverbal mediums for the human creative faculty. Goods are the visible part of culture, and there will indeed always be luxuries as rank will always be marked. Basically, though, argues that goods are a type of social communication, and are the medium through which social relations are carried out. This book tries to distance itself from the theories of moralists who say "stuff" is universally bad.

Interacts With:

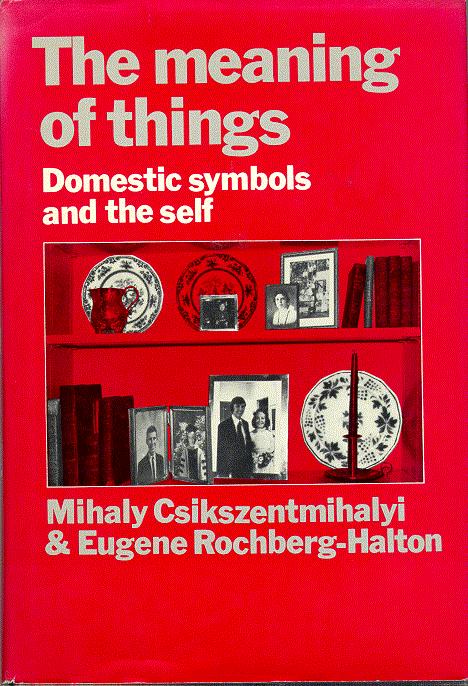

Any book that views consumption and material culture as a social phenomenon full of meaning and identity construction: Meaning of Things,

This point of view is interesting, but in some ways it can come off as a bit too apologetic about/corrective of consumer culture. They sell goods and things as vital elements of identity and social connection, yet what about the very real moral, ethical, and environmental concerns that are connected to excessive consumption - can these really be avoided? It's hard to argue with something that they argue is vital to our very sense of humanity, but there is something a bit sick about people who place such a strong emphasis on construction of self and of status via things. In some cases, I think you can and should judge such excessiveness.