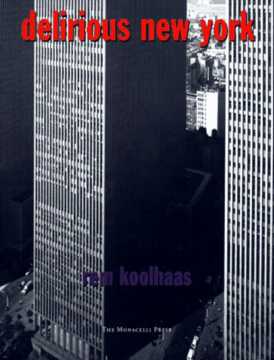

Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (1994 [1978])

By Rem Koolhaas

Synopsis: This book basically sees Manhattan as a "theatre of progress" and mythical fantasy laboratory immersed in the "culture of congestion." It argues that Manhattan is a pinnacle of the artificial, and that its massive congestion is its own brand of urbanism. The book comes across as somewhat of a "fuck you" to Modernist Puritanical "order." Includes sections on "Coney Island: The Technology of the Fantastic" (theme parks of Coney Island as obsessed with the artificial; machines and lights; creation and destruction; Dreamland and its bizarre Lilliputia land of midgets and skewed morality - i.e. promiscuity, homosexulaity, nymphomania, etc.); "The Double Life of Utopia: The Skyscraper" (Manhattan skyscraper born 1900-1910 as a "utopia device for the production of unlimited numbers of virgin sites on a single metropolitan location" (83); tall buildings as laboratory islands and entire own world, i.e. Waldorf Astoria; Harvey Wiley Corbett and his plan for an ultra-ultra dense Manhattan; "the hotel" as a plot in itself - providing world of change encounters); "How Perfect Can Perfect Be: The Creation of Rockefeller Center" (yet another island; Roxy Theatre as producing "synthetic sunrise" (which Koolhaas loves); all as "anti-authentic;" Rockettes as a new breed of pure abstraction); "Europeans: Biuer! Dali and Le Corbusier Conquer NY" (Salvador Dali's "paranoid critical method; Corbu's attempt to pretend NY doesn't really exist so he can "create" his radiant city; Koolhaas hates Corbu as his plans drain NY of its lifeblood and congestion). This book is basically a tribute to the crazy chaos of New York.

Interesting Specifics:

Dreamland was designed as a place "to appeal to all classes" (45). 1911 = Dreamland burns down.

At this time, Modernism was all about an absence of color, and Dreamland was all white (46).

The Waldorf-Astoria was an attempt at the greatest hotel of all time - massive and all-encompassing (145). It was the focus of many 1930s Hollywood films - hotel is a plot, a world presenting myriad opportunities for random encounters at any time (148-50).

In reference to the Rockettes, I think: "Beyond sex, strictly through the effects of architecture, the virgins reproduce themselves" (217).

Interacts With:

This is a great contrast to Nature's Metropolis as Koolhaas views the city as totally unnatural and never even ventures that it could be related to nature at all.

Amusing the Million

I guess it's kind of a positive postmodernism is cool thing? Though don't know if you could really call NY urbanism "postmodern." I should maybe check again to see how "pomo" positive this guy really is - or even how pro-NYC he is. It's kind of a passionate, stream-of-consciousness kinda thing. Fun!